This will be the end of the line for the back-and-forth between Barak and me, so let me thank Barak for his very thoughtful and cordial correspondence on these interesting questions. This is not a moment to say “see you in court,” but to hope that our dialogue has furthered our respective understanding of the issues.

In earlier posts, I hinted that application of the antitrust laws to rabbinical or pastoral hiring practices would run afoul of the Establishment Clause, particularly in light of the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church, which recognized a “ministerial exception” to the application of antidiscrimination law to the hiring of religious ministers. In my view, a fair reading of Hosanna-Tabor would prevent an antitrust suit involving rabbinical hiring. However, for purposes of this post, I would like to respond more generally to Barak’s claim that “entanglement” concerns lead to “Establishment Clause creep,” insulating from legal review the harmful decisions of religious organizations.

Barak’s concerns over “creep” fall into two categories. One concerns the externalization of costs from religious organizations to others–his example of people cutting across the neighbor’s lawn to get to church. This is an easy case for me, because religious organizations should not be allowed to justify externalizing costs onto others in the name of religious independence. Of course, one could argue that all purely private activities end up externalizing costs or benefits onto others (i.e., functional families make for happy neighborhoods, dysfunctional ones for unhappy neighborhoods), but I’m confident that sensible lines can be drawn between what is mostly internal and what is significantly external.

What about cases where the harms, if any, are all or mostly internalized within the religious organization or by its members? Consider two examples: ritualistic human sacrifice of willing victims and regulations applied to require churches to install wheelchair ramps. In neither of these cases is the Establishment Clause or free exercise defense plausible. In the human sacrifice case, the act is morally abhorrent and the legal prohibition clear. Any ostensible free exercise interest is outweighed by the state’s legitimate interest in preserving human life and there is no danger of entanglement. In the wheelchair ramp case, the legal requirement concerns a physical structure far enough removed from the purposes and values of the religious organization that there is little risk that enforcing the building code would require civil authorities to inquire into the existential purposes of the church and their relationship to the civil law.

Not so for antitrust law (and perhaps other business torts as well). Antitrust is not justified on the grounds that collaboration among rivals is inherently immoral or injurious. Rather, it is justified on instrumental grounds–that competition among business firms tends to increase output and decrease prices to the benefit of consumers. As I said in earlier posts, it’s awkward to apply this assumption wholesale to religious organizations, since many such organizations would resist the idea that they are ordinary economic actors or exist in order to achieve a better deployment of society’s scarce social resources. And most religious groups would strongly deny that they would function better if they fostered internal economic rivalry.

For example, for mendicant orders like the Franciscans, the “employees” are bound to an oath of poverty. They are expressly prohibited from being Chicago School “rational profit-maximizers.” If the Franciscan order put in place rules to prevent local parishes from trying to attract Franciscan monks through promises of higher compensation, that would run counter to the Sherman Act’s assumption that economic rivalry results in an optimal allocation of resources. But I’m doubtful that the Sherman Act’s assumption generally holds in the religious organization context. And, even if it sometimes might hold, it would be troubling to ask courts to sift through the evidence on different religious organizations to determine when it does hold and when it doesn’t–when the existential purposes of a particular sect would be furthered by greater economic rivalry and when they would not. That, in my view, would raise serious entanglement problems. Do we want courts deciding what degree of poverty is appropriate for Franciscan monks?

[I’m amending my post from last night to add a further anecdote from the Christian tradition that illustrates the problem. In the gospel accounts, when Jesus enters the temple he finds merchants engaging in commerce and drives them out with a whip, saying that God’s house should be one of prayer, not of thievery. Many churches today are reluctant even to sell sermon tapes or Christian books in the church foyer because of this and similar admonitions. That this is a concern in the Christian tradition does not make it universally a concern, but it does suggest an entanglement problem if courts were to undertake an inquiry into when commercial transactions are permissible, and when not, within a particular religious tradition.]

In short, I’m less concerned about Establishment Clause creep than about antitrust creep. Economic rivalry is good sometimes, but not always. Unlike Barak, I wouldn’t start with the assumption that antitrust law should apply universally to all human endeavor unless a special exception is warranted. I would start with the assumption that antitrust should apply to business and commerce and only extend it to other endeavors if the case for extension were clear and unencumbered by competing religious, social, or moral values. As to rabbinical collusion, I’m not persuaded that case has been made.

Like this:

Like Loading...

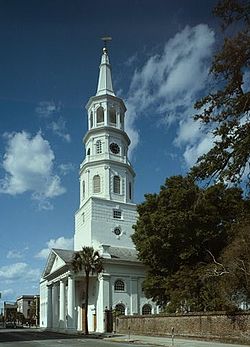

This time it’s in South Carolina. Yesterday’s Wall Street Journal

This time it’s in South Carolina. Yesterday’s Wall Street Journal